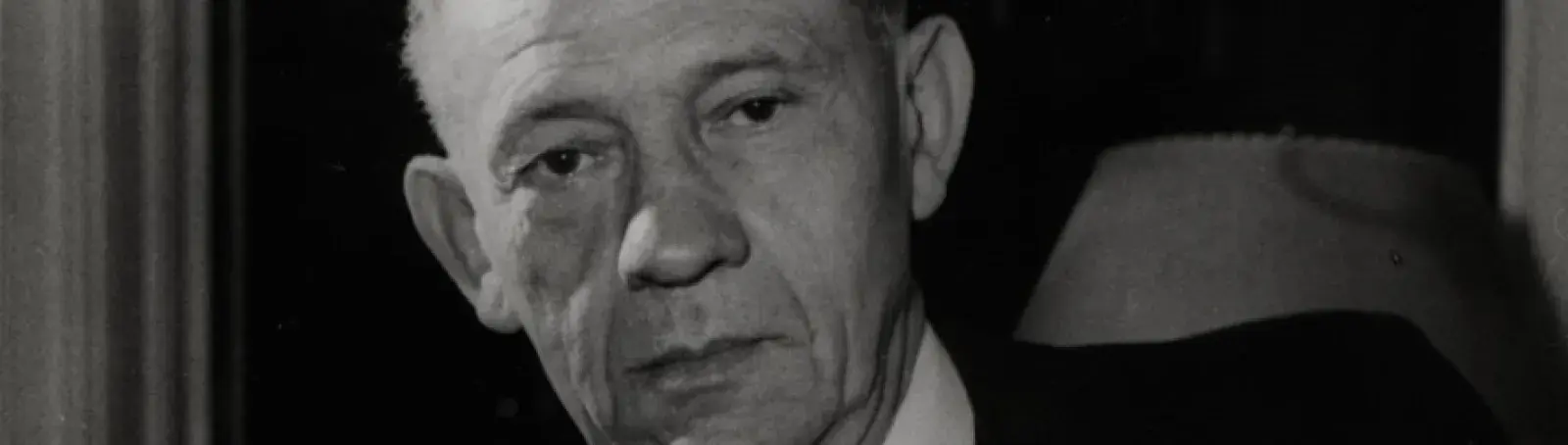

Laszlo Lajtha (1892- 1963) was one of the greatest Hungarian composers of the first half of the twentieth century, and he also made important contributions to ethnomusicology, music pedagogy, and international cultural diplomacy. During his lifetime he was mentioned (predominantly in France) together with Bartók and Kodály, who were a decade older: 'Jes trois grands hongrois' - the three great Hungarians. Because of his opposition to communism, after 1948 his works were hardly ever played in Hungary. In recent decades, musicians, scholars, and the public have begun to rediscover his distinctive oeuvre.

He was born on 30 June 1892 in Budapest. His talent showed itself very early on: he was already composing at the age of seven. He took piano lessons with Árpád Szendy, but he also studied under Béla Bartók at the Budapest Music Academy, where he graduated in composition in 1913 as a student of Viktor Herzfeld. In 1918 he obtained a doctorate in political science and jurisprudence. In 1909 he spent three months in Leipzig, where he heard Bach performances in the Thomaskirche. In Geneva he took piano lessons with Stavenhagen, a pupil of Liszt's. Until the outbreak of the First World War, he spent six months each year in Paris , where Vincent d'Indy not only taught him, but introduced him to the musical life of Paris. The young Lajtha was present at the premieres of works by Debussy, Ravel, Stravinsky, and others. This time spent in Paris, and the friendships he forged with the artists there, were decisive in the formation of his idiom as a composer. He spent the four years of the First World War at the front as an artillery officer, which interrupted his promising career as a pianist, though his ambitions as a composer were in any case stronger. Béla Bartók considered this 28-year-old composer to be one of the most promising in Hungary: ' Apart from Kodaly and Lajtha we [Hungarians] have no valuable composers,' he wrote to a British musicologist. Lajtha 's early compositions are characterized by bold innovation. Later on he pursued a different path, and he himself said that his aim was 'after all the isms, to bring music back to the field of humanism.' His main musical models and points of reference remained J. S. Bach, Haydn, Mozart, and the great French masters: Debussy and Ravel. Lajtha gave opus numbers to 69 compositions. One of the most important threads of his oeuvre consists of the nine symphonies. Maurice Fleuret believed Lajtha to be 'one of the greatest symphonists of the twentieth century ' . He also wrote other works for orchestra, chamber orchestra, chamber music (including ten string quartets), solo pieces, songs, choral works, sacred music (including two masses and a magnificat), three ballets, one opera buffa, music for four films, and many folk music arrangements. In 1928 he signed his first contract with Leduc of Paris, which later became his permanent publishers. His orchestral and chamber works were often premiered in Paris. In 1930 Elisabeth Sprague-Coolidge, a famous American patron of the arts, commissioned a string quartet from him. The work won international acclaim. Following this his works were played worldwide. Lajtha was also a member of the Societé Triton, founded in Paris in 1932, and the first piece in the society's opening concert was his Shing Quartet No. 3, which had won the Coolidge prize. In 1947 he travelled to London for a year, to compose the soundtrack to Georg Hoellering's film Murder in the Cathedral, based on T. S. Eliot's verse drama. While he was there, communist dictatorship took hold in Hungary. Lajtha was warned of the danger, but in vain; love for his country drew him home to Budapest. He lost his jobs, he was denied a passport for 14 years, and the only way to communicate with his sons in the West was by post. In 1955 he was the first Hungarian composer to be elected a member of the French Academie des Beaux-Arts (to the seat previously occupied by George Enescu, the deceased Romanian composer).

He began collecting folk music (following primarily in Bartók's footsteps) in the 1910s, and continued to his death. In 1913 he joined the Hungarian National Museum, where initially he was curator of the musical instrument collection, and later directed the folk music department. In 1946 for a short while he was director of the Ethnographic Museum. In 1951 he received a Kossuth Prize in recognition of his research work, which was outstanding primarily in the field of collecting instrumental folk music and historical folk music. His most important publication on folk music is the series Népzenei Monográfiak (Folk Music Monographs).

In 1919 Lajtha was appointed a teacher at the National Music School. After the end of the Second World War he was director of this institution for a few years, and he was the last director-general, when the institution was reorganized in 1949. He taught for three decades, a total of 11 subjects. His pupils included internationally recognized artists such as conductor János Ferencsik and violinist Vilmos Tátrai, both of whom often performed his works.

From 1935 to 1938 he directed the music broadcasts of the Hungarian Radio open university, and from 1945 for one-and-a-half years he was music director of Hungarian Radio. He played an important role in the reorganization and expansion of the Hungarian Radio orchestra. Typically for him, while he was director he forbade radio performances of his own works.

His work in cultural diplomacy began in 1928, when a lecture he gave in Prague attracted a great deal of attention at the First International Folk Art Congress held by the League of Nations Committee on Intellectual Cooperation (the predecessor of UNESCO). In 1930 he was elected chairman of the folk music and folk dance division of the International Committee on Folk Art and Folk Traditions, and received several commissions as an expert. In 1947 he participated in the foundation of the International Folk Music Council (operating under the auspices of UNESCO) and was a member of the organization's board of directors until his death. During the time the communist government in Hungary refused to allow him to travel abroad, he was music consultant at the French Institute in Budapest, and was effective in promoting contemporary French music in Hungary.

He died on 16 February 1963 in Budapest.

(Solymosi-Tari Emőke, fordította: Richard Robinson. Forrás: BMC CD 189)